Crucifixion myths debunked by doctor at Catholic Medical Association

Dr. Thomas W. McGovern presents "Another Doctor at Calvary: New Insights Cast Doubt on the "Settled Science" of Crucifixion" during the 87th annual education conference of the Catholic Medical Association on Saturday, Sept. 22, 2018 at the Renaissance Dallas Addison Hotel. (NTC/Kevin Bartram)

ADDISON — Through scripture, historic records, archeology, at time graphic depiction, and even graffiti, Dr. Thomas McGovern discussed and dismissed myths concerning Jesus' crucifixion at Calvary.

A Fort Wayne, Ind. skin cancer surgeon and host of the radio show “Doctor, Doctor,” McGovern spoke Sept. 22 in Addison, during the final day of the Catholic Medical Association's Annual Educational Conference.

During his junior year of medical school, McGovern also taught religious education to sixth graders.

“I thought, wouldn't it be interesting to teach my students about the sufferings our Lord went through on the cross?” McGovern said.

McGovern acquired an article, “On the Physical Death of Jesus Christ,” from his pathology professor, Dr. William Edwards, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 1986. McGovern also turned to A Doctor at Calvary: The Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ As Described by a Surgeon, a 1950 book penned by French surgeon Pierre Barbet.

Following years of research into the matter, McGovern said he came to doubt several of the findings put forth by Barbet and Edwards, whom McGovern considers his mentor.

A stumbling block, McGovern argued, is that they and others investigating the crucifixion often simply cited earlier findings and conclusions without looking into them.

Edwards, for example credited Luke's account of Jesus' sweat being like “great drops of blood” to having originated through Jesus' sweat glands. Not so, McGovern said.

“This is from Dr. Edwards' article,” McGovern said. “As a result of hemorrhage into the sweat glands Jesus' skin became tender and fragile.”

More likely, McGovern said, is that Jesus's blood and sweat did mix, but on the surface of His skin, not within His sweat glands.

Hematidrosis, the probable result of blood cells leaking through capillaries, provided the more likely cause, McGovern said.

More than 20 such reported cases since 2013 back such claims, he said.

Victims in such cases often display bleeding in areas absent sweat glands such as tear ducts, fingernail beds and the tongue.

“From pictures and biopsies we see that blood somehow seeps out the skin and mixes on the surface with sweat,” McGovern said. “It's still bloody sweat; it just doesn't happen under the skin.”

It's doubtful as well that the scourging of Jesus occurred at the Antonia Fortress, a compound of military barracks in Jerusalem. Instead, the scourging probably took place at Herod's palace.

“If you're Pontius Pilate, you are over [rank higher than] whichever Herod is there at the time,” McGovern said. “When you come to town, are you going to stay in these little military digs or are you going to take over the best place in town?

“Contemporary historians indeed tell us that when Roman prefects came to town they always stayed at Herod's palace, not Antonia Fortress. How many generals even today go live with the grunt troops when they visit somewhere? They don't. Even the Gospel of Mark says Jesus was taken to the praetorium, that's a palace, when he was scourged.”

Historic accounts of crucifixions, the practice of which dates more than 500 years before Jesus' birth, indicate that Jesus never carried a two-part cross. He more likely carried the cross bar, which weighed about 15 pounds.

“St. Helena went to Jerusalem in the 320s in search of relics of the crucifixion, which she brought back to Rome including the cross bar believed to have belonged to the Good Thief, which weighed about 15 pounds,” McGovern said.

The cross bars were then affixed to cross poles, which were left standing in place, McGovern said.

“Anything I could say would be mere speculation,” McGovern said of how victims were placed on a cross. “There's no details or nothing written about that, unfortunately.”

Evidence from the Shroud of Turin indicates Jesus was nailed through the wrists, not the palms, he said.

Ancient graffiti depicting other crucifixion victims also indicates such and that Jesus's feet were nailed not one on top of the other but to the side of the cross through His heels.

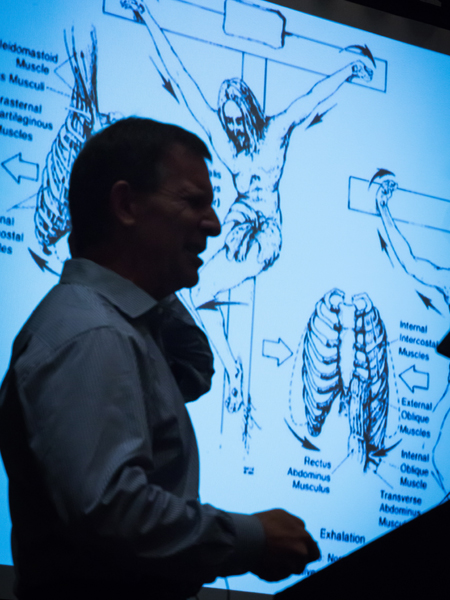

Jesus also probably did not die of asphyxiation, as many believe.

Barbet based such suffocation theories on aufbinden, a World War I technique whereby men were hung by their bound wrists above their heads and feet off the ground. In crucifixion by contrast, the victims arms are basically horizontal and their feet supported. Jesus also cried out loudly the moment before His death, McGovern said, something a suffocating person could not manage.

Jesus likely died from heart failure through a mix of exhaustion, shock, blood loss, pain, lack of fluids, and other factors, McGovern said.

Inquiry into the crucifixion, while interesting if somewhat gory, also teaches that our sufferings, as Christ's sufferings, are not in vain.

“John Paul II said each man must share in the redemptive suffering of Christ, which has saved all people,” McGovern said.

“Through that we can actually impact someone else's eternity. Yes, you can become daily students of the school of suffering, and you know what we call graduates of the school of suffering? We call them saints.”

Conference attendee and Houston physician David Daniel said he found McGovern's talk interesting.

“So much information about the crucifixion is taken at face value and ascribed almost to religious belief when, if you look at it, it's not particularly scriptural-based or particularly strongly science-based,” Daniel said.

Fellow Houston physician Carla Falco agreed.

“The asphyxiation theory, which I thought was the predominant theory, was interesting,” Falco said. “It wasn't until today I heard the different theories, and I was pretty convinced by his arguments.”