Extraordinary heroes: be the hero your child needs

Do you know any extraordinary heroes?

In the 1950s my brothers, sister, and I followed Superman’s adventures in the old George Reeves TV series. Our parents regarded this with amused resignation, knowing it gave us pleasure to watch Superman and other Hollywood heroes.

We’d be gripped with fear whenever Supes was doused with lethal megawatts of electricity, had an atomic bomb dropped on him, or — worst of all — was exposed to Kryptonite. When such catastrophes befell the Man of Steel, Papa would glance up from his crocheting and puckishly — perhaps hopefully — remark, “Well, that’s the end of Superman. I guess we won’t have to watch him again next week.” We children howled at this callous disregard.

To be fair, Papa didn’t play favorites. His impish comment was also directed at Hopalong Cassidy, cornered and shooting it out with desperadoes; or Rocky Jones, in the midst of a power dive after the sparklers powering his rocket ship fizzled out; or when Robin Hood, tricked and captured by the Sheriff of Nottingham, was sentenced to hang.

After a while, it dawned on us that Papa enjoyed these shows as much as we did. His disparaging interjections became a family ritual that, eventually, we children eagerly awaited. We were all caught short when Davy Crockett actually did die at the Alamo and did not come back the next week. Papa had expected Disney to rewrite history.

Papa, the original DeForeest for whom my son, DeForeest III, is named, was a passionate amateur genealogist. There was no Ancestry or Find A Grave back then. He spent hours at the Central Library in downtown Los Angeles, keeping up a continuous correspondence with Wrights, Van Dusens, Quicks and other families as he put together the Wright family tree. His writing was light but insightful, redolent of intriguing details and often humorous asides. His proudest moment came when he proved his relationship to George Wilson, a captain of artillery during the Revolution.

In a more perfect world, Papa would have been a college professor, writing enjoyably readable books about American history. Instead, after his stockbroker father died, Papa left school after eighth grade to manage his mother’s rooming house and take care of his beloved younger brother, David. Papa read omnivorously. He taught himself to crochet as he recuperated from a missed stroke while cutting firewood, the axe cleaving into his left shinbone.

At seventeen, Papa was employed as an accountant at an iron smelter in New Jersey. In 1936, during the Great Depression, he made his way to Los Angeles to find work as a butler for the family of legendary Los Angeles real estate broker, Frank D. Tatum whose family remained lifelong friends. My father later became an accountant at Western Truck Lines. He continued working there for 31 years, retiring in 1975.

Again, in that same perfect world, Mom, Valentina Carkoski — Viola to her family, husband and friends — born in Elyria, Nebraska, would have gone to nursing school, maybe even become a doctor. Instead, her mother, Helen, died in 1931 when Mom was ten, leaving her with younger sister, Virginia, and father, Leon.

This was the era of the Dust Bowl when farms and ranches went belly up as clouds of choking dust and dirt swept over the plains. The family took up residence at the then derelict Fort Hartsuff, near Burwell, Nebraska. Grandpa Leon struggled to find employment but jobs were few and far between. During the winter of 1934 the family survived on little more than stored-up potatoes which the girls tried to find creative ways to cook. The potatoes were augmented only occasionally with game when Grandpa could find any to shoot amid the snowdrifts.

On a visit to the now-refurbished fort in 1982, Mom came upon an exhibit in which a thick coat was identified as belonging to an early settler. She recognized it as her father’s.

Mom dropped out of tenth grade to work part-time in a beauty parlor and babysit children in town, raking in a quarter here, a half-dollar there. Arriving in California when she was 20, she became governess for the children of Donn Tatum, Frank D’s son.

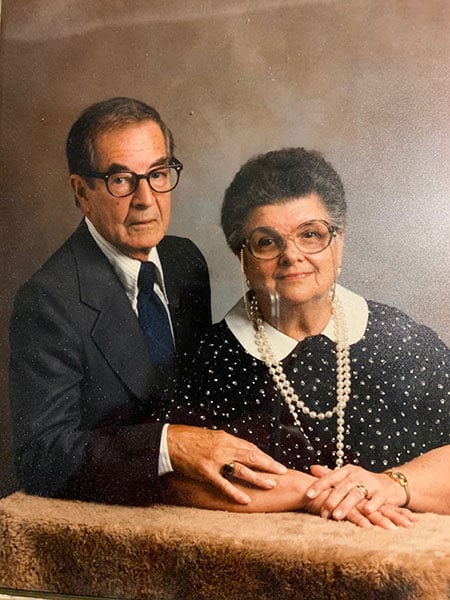

In the course of their duties, in 1941, DeForeest and Viola met and married the next year. Papa was an academic, a realist with a rich streak of romantic idealism. Mom was blessed with hard-headed common sense. Amazingly, with love, they fit together quite well.

Papa, a sometime Methodist, had already become an ardent Catholic in 1940. Mom was a lifelong Catholic but, living in rural Nebraska, saw a priest only once a month for Mass. Her parents, along with numerous aunts and uncles, taught her prayers and devotions brought from Poland. Mom told me, a few years before she died, that Papa had really taught her about the Church. The only formal training she’d had before was when nuns had come to Elyria to instruct the seven-year-olds for First Holy Communion.

In time DeForeest and Viola produced Helen, DeForeest, Jr., me, and William. A typical Catholic family, we attended Mass each Sunday, prayed the Rosary on trips, and we boys became altar servers. Helen became a religious sister in the order of the Immaculate Heart of Mary until they disbanded.

Only later we discovered how Mom and Papa reveled in our sometimes hilarious adventures. Many family friends told us how our parents often declared that raising us was the happiest time of their lives.

Viola and DeForeest continued in love for over 51 years. Mom was a tough Pole like Pope John Paul II, whom she revered. Severely hobbled by arthritis and yoked to an oxygen tank, Mom found the strength to nurse my father during his last years, even days after sustaining a radical mastectomy. Papa died of Alzheimer’s disease in 1993. Mom joyously watched her grandson grow up, enjoying another youngster in the family home in Hollywood until she died in 2009.

My parents survived the hardships of the Great Depression and the butchery of a world war. They grew up before automatic welfare benefits, before entitlements, before stimulus checks — before America’s culture swept into decline. If you said something about their being heroic, you’d get a quizzical look in return. “We did what had to be done to survive.”

Yet, in overcoming their hardships, my parents, along with many others in the first half of the 20th century, proved themselves extraordinarily heroic, displaying the innate maturity, tenacity, and integrity that originates in the essential goodness of the God whose love they reflected so well.

Nowadays swinish families, not heroes, are depicted holding forth on television, reveling in uncouth behavior, destruction of property, and sexual depravity. It is commonplace to hear of parents abusing each other and their children, even to the extent of murdering babies in the womb. It is, to say the least, extraordinarily difficult for children to find extraordinary heroes today.

So, parents, this is your chance. Don’t give in to this bizarre culture. With God’s merciful aid you can be the extraordinary heroes your children need and will look back on fondly, remembering the love that suffused your families.

You may not wear a cape or a cowl but you have “powers and abilities far beyond those of mortal man” from the sanctifying grace that comes with the sacrament of Matrimony, powers lavishly bestowed on moms and dads by the good God so you can make your family a holy family.

Don’t miss any opportunity to let your children know how very much you love and enjoy them since, as Jesus told us, “Their angels continually behold the face of My Father in heaven.” Give your children a chance to say they knew extraordinary heroes, a super man and a super woman — their parents.

Behind his glasses Sean M. Wright is mild-mannered journalist observing moments of grace in everyday life. An Emmy nominee and member of the RCIA team at Our Lady of Perpetual Help parish in Santa Clarita, he answers comments at [email protected].