Health care rooted in the Catholic Faith, Part 2: God Bless Texas

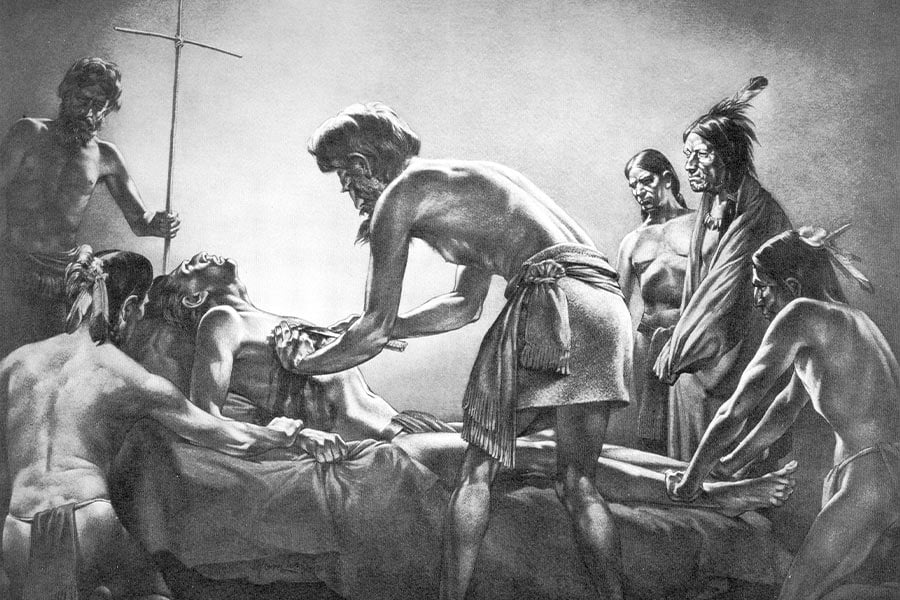

Cabeza de Vaca performs the first recorded surgical operation in North America in 1535 in this painting by Tom Lea. (Courtesy Moody Medical Library, UT Medical Branch, Galveston)

Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, the first person to heal the sick in the name of Christ in present-day Texas, had no intention of doing so when he set sail from Spain for the New World in June 1527 with the Pánfilo de Narváez Expedition. As first lieutenant, de Vaca’s primary role was to serve as treasurer in the 5,000-mile journey to claim new land for Spain along the Gulf Coast.

By 1532 — after shipwrecks, drownings, starvations, and attacks by the native inhabitants — only four men, including Cabeza de Vaca, were alive. The explorer eventually lived to tell about his 2,500-mile trek through Texas and the Southwest.

In his dealings with the Native Americans, Cabeza de Vaca combined his passion for Christ, limited knowledge about medicine, and will to survive to heal the sick. In doing so, he found favor with the indigenous people.

Cabeza de Vaca heals the sick

“The way we treated the sick was to make over them the sign of the cross while breathing on them, recite a Pater Noster and Ave Maria, and pray to God, Our Lord, as best we could to give them good health and inspired them to do us some favors,” the survivor wrote in his journal.

Remarkably, in 1535, Cabeza de Vaca removed an arrowhead lodged deep in the chest and in dangerous proximity to the heart of a Native American. The experience was recorded by the explorer and was documented centuries later in the New England Journal of Medicine as the first recorded surgical procedure in the Southwest.

On Dec. 27, 1973, in that medical journal, Dr. Jesse E. Thompson, M.D., a medical pioneer himself, wrote of Cabeza de Vaca:

“His usual method of treatment was a laying-on of hands and fervent praying, to which the Indians responded miraculously. However, with what tools he had, Cabeza de Vaca also practiced surgery when necessary, and in one historic operation in 1535, removed an arrowhead from deep in an Indian’s chest (sagittectomy). This surgical cure made him famous among the Indians and was responsible for his eventual safe return to civilization.”

Franciscan friars open infirmaries

The earliest forms of organized group health care in Texas occurred at the Spanish missions throughout the area in the 17th and 18th centuries. At the missions, where life was centered on the Church, Native Americans were taught to farm and ranch, and become proficient at practical trades in an effort to assimilate them to the newly settled communities.

Franciscan lay brothers and priests not only served the Church, but also considered themselves protectors of the Native Americans. For that reason, they took on the role of caregivers. They tended to the needs of the sick among indigenous people, along with soldiers and others who lived in and around the missions. The Franciscans administered the care at mission infirmaries.

The Franciscans, in fact, likely spent a lot of time caring for the sick, with major outbreaks of smallpox, influenza, malaria, measles, and other diseases occurring regularly.

In 1806, the friars at San Antonio de Béxar mission in San Antonio were controlling a smallpox outbreak by administering inoculations against the viral disease.

Religious orders of women establish Texas hospitals

The hospital system in Texas advanced unintentionally as a response to health emergencies after the Ursuline Sisters of New Orleans arrived in Galveston in 1847 to establish their Ursuline Academy. Its purpose was education, not health care.

The school opened in 1854 but closed temporarily in 1857 after students contracted yellow fever. The sisters nursed and cared for students and others sickened by the virus. Then, in 1861, after opening a new wing, the school was converted into a hospital to care for both Union and Confederate soldiers during the Civil War. Once again, the sisters were serving as nurses.

In 1863, in response to hundreds of casualties at the Battle of Galveston, the sisters opened up the entire academy as a hospital and worked to care for the injured and dying. Although it was not their original intention, the Ursulines had established the first war hospital in Texas. Their compassion to care for the sick, as Christ asked, became their mission in a great time of need.

The Ursuline Convent and Academy in Galveston circa 1890. (Courtesy Texas State Historical Association)

It would not be the last time the sisters would be asked to care for the sick, injured, and dying. When a devastating hurricane battered Galveston in September 1900 — with storm surges flooding the coastline with 8 to 12 feet of water, killing several thousand people and leaving thousands more injured — the sisters once again came to the rescue. Seven thousand structures, including 3,600 homes were destroyed, but the Ursuline Academy was largely spared, as it had been built on relatively higher ground on Galveston Island. The sisters opened its doors, and it served as a temporary shelter for about 1,000 residents.

Another order of religious women, the Sisters of the Incarnate Word in Lyons, France, would play a major role in advancing the hospital system in Texas. At the request of Diocese of Galveston Bishop Claude M. Dubuis, the order sent three sisters to the Lone Star State. At the time, the Diocese of Galveston included all of the state of Texas. Through the bishop’s guidance, they would become the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word (CCVI). By April 1867, the sisters built the first Catholic hospital in Texas, a two-story frame building in Galveston named Charity Hospital.

Within three months of the hospital’s opening, the sisters were dealing with a major outbreak of yellow fever that caused their facility to be filled to capacity by mid-August. That same month, one of the order’s original founding sisters, Mother Mary Blandine Matelin, died from the disease. Two doctors at the hospital were also yellow fever victims and died.

By September, the remaining sisters and other health care workers at the hospital had survived the worst.

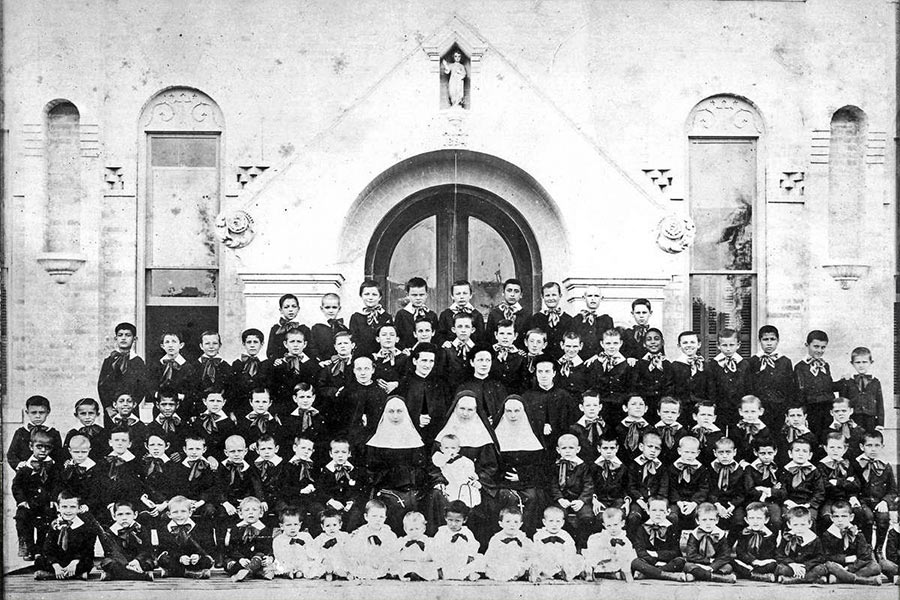

Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word not only excelled in caring for the ill, they also cared for orphaned children. This photo was taken circa 1900 at their orphanage in San Antonio. (Courtesy/Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word)

The Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word developed an unsurpassed reputation for nursing and hospital administration in Galveston. In 1879, the City of Galveston disbanded its own municipal hospital and made arrangements for the sisters to care for its patients at their hospital, which was renamed St. Mary’s Infirmary.

Catholic Church continues to advance hospital system in Texas

Bishop Dubuis knew the labors of the sisters was only beginning in Texas, as health care workers were greatly needed across the state.

In 1869, the bishop sent some of the sisters to San Antonio to open a hospital there. The following year, they had built a two-story brick and stone building, the first Catholic hospital in San Antonio.

The excellent Catholic hospital system that Bishop Dubuis had put in place with the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word continued under Auxiliary Bishop Nicholas A. Gallagher. Bishop Gallagher had taken over administrative duties for the ailing Bishop Dubuis in 1881.

In 1885, Bishop Gallagher tried to keep his predecessor’s momentum moving forward when he strongly urged Reverend Mother St. Pierre Cinquin, CCVI, to visit the railroad infirmary in Fort Worth. He hoped she would send sisters to take over greatly needed nursing duties.

Realizing the need for medical care was grave in Fort Worth, the reverend mother sent 11 Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word to serve in Fort Worth.