Inside job: “Rockin’ Roger” Hinesh helps others use second chances

After beating his addiction to alcohol and drugs, Roger Hinesh, a Boys Town alum, has devoted his life to encouraging convicts and substance abusers to turn their lives around. (NTC/Juan Guajardo)

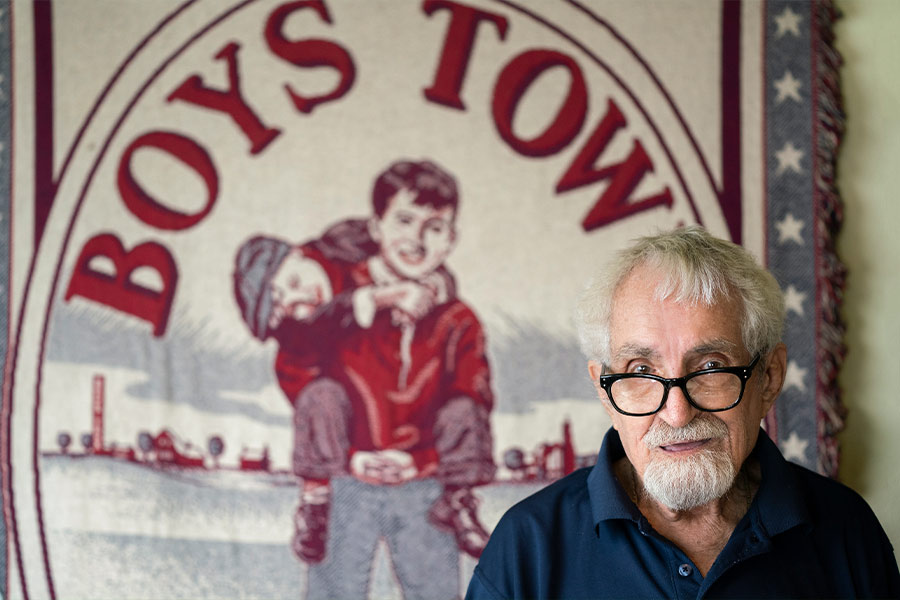

A Boys Town banner holds a prominent position in front of Roger Hinesh’s home in Wichita Falls.

Enter his home, and Boys Town memorabilia is displayed on every surface. From the shirt that he wears (plus the one on the ironing board) to the decorations on the wall, each available area has a poster, ornamental plate, artwork, photo, blanket, or correspondence regarding the orphanage in Nebraska. Between each item — only an inch or two of space. The prize of his collection is a bronze statue of Father Edward Flanagan, founder of Boys Town in Omaha, Nebraska.

Father Flanagan established the home for wayward boys in 1917 with the philosophy, “There’s no such thing as a bad child. There is only bad environment, bad training, bad example, bad thinking.”

Hinesh hasn’t counted how many Boys Town keepsakes he has. As many as 100? He responded, “Oh, much more than that.”

But Hinesh is not a typical collector. He explained he likes to surround himself with the positive, because for years he wallowed in the negative.

His story of 81 years begins in Omaha when his unwed mother gave him up for adoption. He spent much of his childhood in an orphanage until he came to “the home of my heart,” Boys Town, at the age of 14.

He remembers a few years of a nearly idyllic life: going to school, working in the bakery, serving at Mass, singing in the choir. He found a family among the boys, and a few of the priests were father figures to him.

Then, he discovered rock ‘n’ roll.

At 18, he won a few dance contests and headed to Hollywood. He met some success and danced in 11 movies, most notably Elvis Presley’s “Jailhouse Rock.” He remembers Elvis instructing him, “You’d better move it, Rockin’ Roger.” The nickname stuck.

Between movie assignments, Rockin’ Roger worked in the recording industry, evaluating new musical groups in nightclubs.

Within a few years, he was drinking too heavily to hold a steady job. “It was just one day and one bottle at a time,” Hinesh recalled. Addicted to alcohol and drugs, he turned to burglary to support his habit.

His cycle of addiction, crime, and imprisonment continued for the next 20 years in Nebraska and Texas.

Hinesh plunged to rock bottom during his third incarceration when he was placed in solitary confinement. He came to understand that his current path would lead him to spend the rest of his life in prison. He realized his life needed to change, and change began with him.

Hinesh wrote of the experience in a 2006 newsletter to the Boys Town National Alumni Association. “I got to a point where I was about to lose my mind when I heard a voice saying, ‘You’re not a bad boy. It’s only bad thinking, bad examples.’ This voice brought back memories of Boys Town and Father Flanagan.”

Over the next year, a prison-based Alcoholics Anonymous chapter helped prepare him for his 1975 release from prison at the age of 37. One of his first stops afterward was Boys Town.

“My life’s purpose soon started to change. I started talking to kids throughout the country about making wrong decisions. I actually went back to the Texas prison in 1977 as a guest speaker,” Hinesh shared in the alumni newsletter.

For 46 years, Hinesh has “trudged the happy road of sobriety” and spoken to hundreds of inmates, parolees, and addicts about staying sober. “I have learned that change is an inside job. You have to open your heart and want to change,” he said.

He hopes his story is an inspiration. Because he’s successfully transitioned from addiction to sobriety, and from prison life to the outside world, he wants others to know, “If I can do it, so can you.”

Back at home, a crocheted blanket created by prisoners lays on his bed. It repeats the message he shared with the inmates many times, “It’s an inside job, baby.”

He also talks with students, hoping to prevent them from facing the same problems he did in his youth.

Counseling addicts in prison has taken much of his time and discretionary income. His travel expenses have come from wages he earned in the maintenance department of Midwestern State University, where he worked from 1985 to 2000.

Although he hasn’t collected travel reimbursement from the state, Hinesh received something more valuable. Governors of the states of Nebraska and Texas have each issued Hinesh an official pardon in gratitude for his work as a mentor to inmates.

The Sacred Heart parishioner gives credit to God for turning his life around. “Nothing is possible without God,” he said.

He also recognizes Fr. Flanagan, who dedicated his life to giving youth second chances. “He made a difference in a lot of people’s lives, especially mine,” he said. Moving into Boys Town was a second chance for Hinesh. And in the despair of solitary confinement, lessons from Boys Town in spirituality and morality illuminated the way forward. Hinesh has joined those working for the cause of sainthood for Fr. Flanagan, who has been declared a Servant of God.

Surrounded by mementos of his blessings, he said, “I’m grateful that God gave me another chance. So I ask, ‘What can I do for people?’ I give back; I try to make a difference.”