The first martyr: Franciscan friar Juan de Padilla and his mourners passed this way 500 years ago

A photo illustration depicts what Friar Juan de Padilla looked like. He and his companions likely passed through the future Diocese of Fort Worth with both the Coronado and Moscoso Expeditions as early as 1541- 42. (Adapted from Diocese of Dallas photos /1936 Texas Centennial Exposition)

By now, you already know that we have celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Diocese of Fort Worth. Did you realize, however, that the Catholic history of our diocese can be traced back nearly 500 years?

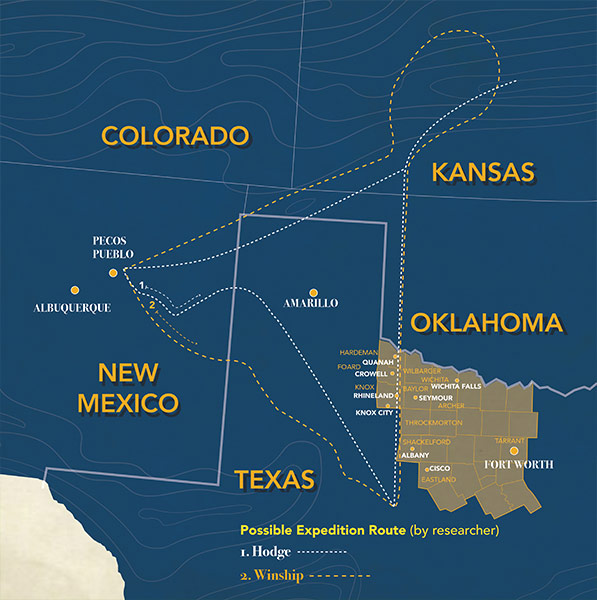

The first martyr in the present-day United States — Franciscan friar Juan de Padilla — likely trekked through the current northwestern boundaries of the Diocese of Fort Worth in 1541 as he traveled with the tenacious Coronado Expedition.

About three years later, holy men with whom he served traveled through our current diocesan boundaries as well, as they mourned the death of Friar de Padilla on their way back home.

The Journey Begins

In 1540, Spanish-born explorer Francisco Vásquez de Coronado assembled 1,000 men, including 240 mounted horsemen, 60 foot soldiers, and hundreds of head of horses, mules, cattle, and sheep. His expedition traveled up Mexico’s west coast, destined for the present-day American Southwest.

Well supplied and armed, Coronado’s objective was to find gold and riches in what is now the American Southwest and to claim this land for Spain. The accompanying friars were intent on bringing Christ to the indigenous people.

Among the Franciscans, in addition to Friar de Padilla, were Friars Marcos de Niza, Juan de la Cruz, and Luis de Escalona.

Failing to find anything of value at the fabled Cibola, part of the Seven Cities of Gold near today’s New Mexico-Arizona border, Coronado turned his attention to the north and east. This time he was in search of another settlement, Quivera, a place he was told was laden with gold. The general location of the mythical city is believed to be around the Texas Panhandle, Oklahoma, or south-central Kansas.

Before he reached his destination in 1541, Coronado split his forces in central New Mexico, northeast of Albuquerque, and pressed onward with 30 select men toward Quivera. The remaining army was sent back to a place they named Tiguex, just to the west. The special mission with Coronado to Quivera included Friar de Padilla.

Some noted historians trace the 30-man journey in search of Quivera as passing through a general area that on close inspection includes Hardeman, Foard, and Knox counties — all within the present Diocese of Fort Worth. Today, Catholics at St. Mary in Quanah, St. Joseph in Crowell, St. Joseph in Rhineland, and Santa Rosa in Knox City all walk in the footsteps of the first martyr in the United States.

Interestingly, another expedition, this one led by Luis de Moscoso, entered the eastern boundaries of the Diocese of Fort Worth about a year later. Franciscan friars traveling with this contingent of 600 men were also among the first to bring the Word of God inside the current diocesan boundaries.

As for Coronado, he never found his riches in Quivera. Like Cibola, tales of the golden city turned out to be another myth. His mission a failure, Coronado began a return march to rejoin his expedition forces in central New Mexico and settle in for the winter of 1541-42. Dejected and injured from a horse fall, Coronado made plans for a final retreat back to Mexico.

Friars de Padilla, de la Cruz, and de Escalona did not share Coronado’s view that the mission had been a failure, as their objectives had been different. They did not want to return, reasoning that their work had only just begun. Unlike Coronado, the friars were not driven to find gold, but to save souls. They had already brought many Native Americans to Christ at settlements along the way and were thankful that so many of these people had accepted Him.

Insight into the hearts of the friars is provided by Carlos Castañeda, noted historian, author, and professor. In 1936 as part of his exhaustive seven-volume work, Our Catholic Heritage in Texas, Castañeda writes:

“Coronado and his men were disappointed, worn out, and ready to leave for New Spain; not so the undaunted sons of St. Francis to whom toils, privations, and hardships were nothing where the salvation of souls was concerned. The courageous and determined [Friar] Juan de Padilla, together with Brothers Luis de Escalona and Juan de la Cruz, told the commander they wanted to stay in the land.”

The author continues:

“The good Padre explained that it was his intention to return to Quivera, where he was sure that his efforts would bear copious fruit in the conversion of the natives. Brother Luis de Escalona, an old and saintly man, wished to remain in Cicuye. He declared that with a chisel and an adze he would erect crosses and baptize the children on their deathbeds in order to send them to heaven. The three Franciscans pointed out that they had the consent of their provincial to stay and labor among the natives.”

The three Franciscans, true to their vocation, followed their hearts and dispersed into the Southwest to continue their ministry.

Friar Juan de Padilla returned to Quivera in 1542, with two Native American lay Franciscans, known as Lucas and Sebastián, and a Portuguese soldier named Andrés do Campo.

The Franciscans, led by Friar de Padilla, were successful in establishing a mission among the Native Americans they had befriended in the High Plains. After two years of ministering to the local inhabitants who were accepting Christ, Friar de Padilla ventured with do Campo and his Franciscan brothers a day’s journey to the east, where they hoped to expand their ministry.

Tragically, the small band of Christians was attacked by a hostile group of Native Americans. It is reported that to gain time for the others to flee, Friar de Padilla knelt down in prayer, intentionally becoming the target of a lethal barrage of arrows. The date of his martyrdom is believed to be Nov. 30, 1544.

Historians have noted that after Friar de Padilla was killed, his companions did not get far before they were captured. The Franciscans and do Campo later managed to escape, and once again the present boundaries of the Diocese of Fort Worth enter the historic picture.

The Trail of the Cross

To mourn Friar de Padilla, the two Franciscan lay members made a large, heavy wooden cross — hewn from native trees — and shouldered it during their on-foot escape back to Mexico. A constant reminder of their fallen brother, the cross also would help them find safe passage back to Mexico, the Franciscans believed.

The journey, according to several historians, would have taken the survivors in a direct path along the Interstate 35W corridor from central Oklahoma or Kansas all the way to Panuco, on the east coast of Mexico. This would place the mourners as traveling inside or near a 200-mile stretch along the eastern boundary of the present Diocese of Fort Worth.

After the group reached Mexico safely, explorers learned of the route the mourners had taken and began following it in their future forays into the interior of the New World. It eventually became I-35, a busy stretch of roadway known today for getting us quickly to our destinations, but unknown for the pathway of holy men mourning the death of the first martyr in the present-day United States.

Historians believe that Friars Escalona and Cruz were also killed in service to the Lord at the indigenous villages where they preached.

While their deaths predate those of the Jesuit martyrs of North America by about 100 years, many people know nothing about Friar Juan de Padilla or his companions.

According to the late Father Don Miller, OFM, of St. John the Baptist Province in Cincinnati, Ohio, Friar de Padilla was the first of at least 79 Franciscans martyred in what is now the United States.

Fr. Miller’s summary of the martyr, who once passed this way nearly 500 years ago, tells us much about the life and death of early Catholics in America and what we can learn from their faithful example.

“Juan de Padilla was motivated more by a desire to spread the Gospel than by fear for his own life,” Fr. Miller wrote. “He reminds us that we do not have much choice about how we will die; however, we have a lot of choice about how we shall live.”