The hidden sacrament: pulling back the veil on the Anointing of the Sick

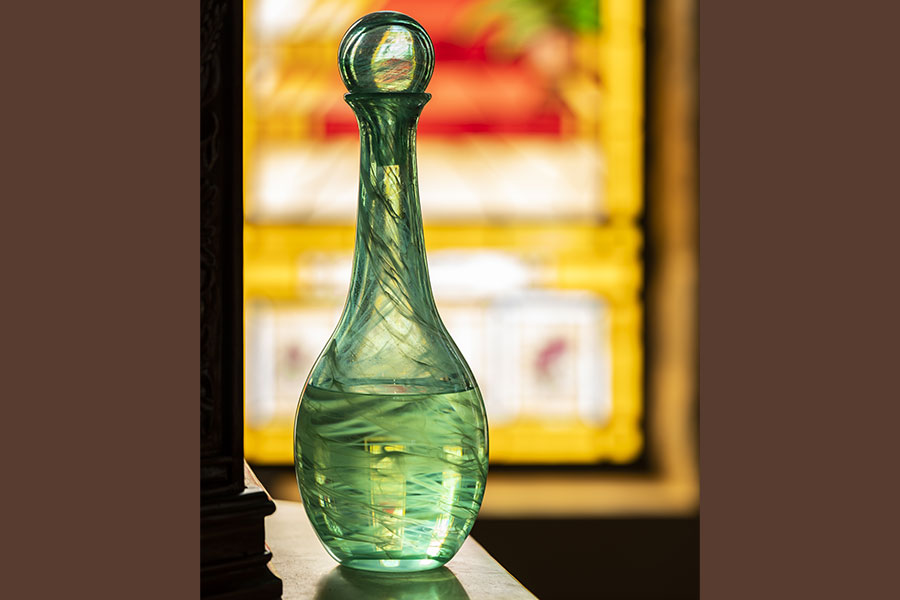

Oil of the sick at Holy Redeemer Parish in Aledo (NTC/Juan Guajardo)

The Anointing of the Sick is one of the most hidden sacraments in the life of the Church. However, a few years ago I was privileged to take groups of students to a local hospice center, and since we had a priest with us, we were invited to gather as he administered the sacrament to a sick woman.

I was so grateful that we were able to witness and participate in this sometimes hidden liturgical work of Christ. Seeing her lying there as the priest prayed over her was to see Christ in action in a way I had not previously seen. I often think of this: how Christ is present in every sacramental action, and how important it is to prepare to encounter Him there.

Who is this sacrament for?

In this sacrament, the people of God are invited, and even urged, to unite their lives and suffering with the passion and death of Christ. In this sacrament, Jesus continues His work among the poor and the sick; He never ceases to give His mercy and grace to those in need.

In the past, it was commonly thought that one needed to be at the doorstep of death to receive this sacrament. One need not wait for such an extreme situation to call a priest. The spiritual dangers of grave illness and the frailty of old age are significant. Knowing this, Christ desires not only to strengthen the faithful but also to unite their sufferings in a special way to His passion and death.

If one is seriously impaired by illness which can lead to death, or if one is about to undergo surgery due to a serious illness, one may seek this sacrament.

It’s widely recognized that friends and families should take care of their sick. That responsibility also includes caring for the spiritual health of their sick loved one. Care should be given so that God’s graces are available to the infirm, if at all possible, before the illness becomes worse.

The qualifier of “serious” is important in this context. This sacrament is not for those who merely catch a cold or are having minor surgery. Seriously debilitating illness comes with fatigue, struggle, and a unique set of temptations that make the sacrament of Anointing of the Sick a very welcome influx of grace. Of course, if a sick person recovers and later falls ill again, the sacrament can be repeated as a new occasion and new need of God’s grace.

What happens during the sacrament?

The sacraments are first and foremost public, not private, matters. It’s important to know what the liturgy consists of and what to expect.

The sacrament of Anointing of the Sick is rather simple in its execution. The priest will begin with an introductory prayer and Scripture reading, wherein we recall that Christ, through His Church, is present in the sacraments. The official prayer of the Church follows. The priest then extends his hands and places them on the head of the believer while reciting a brief prayer. Afterward, the priest will use blessed oil and make a sign of the cross, if possible, on the forehead and hands of the believer. While doing so he will pray the following:

“Through this holy anointing may the Lord in His love and mercy help you with the grace of the Holy Spirit. May the Lord who frees you from sin save you and raise you up.”

Typically, this sacrament occurs in a personal setting. Notice, I did not say a “private setting” because all sacraments are an expression of the public life and ministry of Christ continued by His Church. With this in mind, the Sacrament of Anointing should be celebrated in the presence of family, friends, or other faithful Catholics. Other sacraments and prayers can accompany this sacrament. If one is able, it’s helpful to conduct an Examination of Conscience. In conjunction with this sacrament, the believer (if conscious) may be offered the Sacrament of Reconciliation. If able to swallow, he will be offered Communion or even Viaticum. Even a very small particle or piece of the host is enough. These sacraments prepare the sick to cross over to their “heavenly homeland” (CCC 1525).

The Church is always waiting with open arms to distribute the grace and mercy of God. However, I cannot emphasize enough that the Sacrament of Anointing is best understood as part of a healthy sacramental life. In other words, this sacrament should not be misunderstood as a last-minute, sure-fire, ace-up-the-sleeve to “clean the slate.” Although God willingly offers His mercy even when one is on his or her deathbed, it would be more than imprudent to plan on such a thing, especially when the availability of a priest is not guaranteed.

As Archbishop Fulton Sheen said, “Let no one think he can be totally indifferent to God in this life and suddenly develop a capacity for Him at the moment of death.”

The victory is won

All sacraments find their origin and purpose in Jesus Christ. They serve to provide that which is necessary for salvation for the individual and the Church.

Christ’s title can give us great insight into the meaning, power, and dignity of this sacrament. “Christ” means Anointed One. And while several in salvation history, such as King David, were known as God’s anointed, none share in this anointing in a full and everlasting way except Jesus, true God and true man. When we receive the sacrament of Anointing of the Sick, we do so through the person of a priest by the hand of the very Body of Christ, who healed the sick and the lame and raised the dead. It’s in that moment which we participate in His continued work of healing and saving the world.

At the heart of the Paschal Mystery is Christ’s supremacy over sin and death, which is beautifully expressed in His resurrection. God created man with a body and soul and with the intent of an everlasting relationship with Him. In response to the evil that sin brought into the world, whose ultimate fruit was death, God eventually sent His Son. Death, the ultimate fruit of sin in the world, is often preceded by the suffering of illness and the infirmity of old age. In Scripture, Jesus does not heal everyone that He encounters, but the ones He does are radical witnesses of Christ’s victory over sin and death.

These prophetic signs come to fulfillment by the triumphant passion, death, and resurrection of Christ Himself. In addition, Christ identifies Himself with the sick and the suffering (Matthew 25:36). This, combined with the suffering of Christ on the cross, offers a new dignity to the faithful who suffer — if they are willing to unite their suffering to that of Christ’s (Colossians 1:24).

Misuse of the sacrament

The sacrament is properly understood as one of healing and comes from God, who wishes for our wholeness in both body and soul. If, however, one were to openly deny the fullness of God’s mercy, which necessarily includes repentance of sin, the sacrament should certainly be delayed. Without this willingness for conversion and openness to mercy, the seeking of the sacrament of Anointing of the Sick would be approaching the Church as more of a machine rather than the person of Christ.

And again I stress: seeking the sacrament extremely close to death can be risky in itself, for there is a chance that a priest may not be available for the call.

Viaticum and “Last Rites”

Viaticum is the term used for one’s last Communion, when the believer is close to death. Just as our first Communion should be marked with solemnity and considered a special event, so too should one’s last Communion. In fact, as a baptized Catholic, we have a duty to seek this last sacrament. Canon law states, “The Christian faithful who are in danger of death from any cause are to be nourished by holy Communion in the form of Viaticum.” It is something that the dying faithful are due. And their families should know that they are to receive it and request it from their pastors on behalf of their dying loved ones, at an appropriate time.

It is primarily a pastor’s duty and privilege to administer Viaticum, but any priest may do so. If circumstances require, a deacon or lay person may also offer holy Communion at this important time, but without the other prayers associated with “last rites.”

“Last rites” is an old and common term used to describe the various sacraments, rites, and prayers that may be offered for the dying. Essentially, the principle is that the Church desires to give every good possible to the dying in hope they will stay faithful to the very end. While this is not particularly emphasized today, the Church has a long tradition of encouraging her children to prepare for the “hour of our death.”

In continuing that tradition of offering every sacrament available according to the circumstances, along with prayer and even a Litany of the Saints, the Church expresses concern for her children who are ending their earthly pilgrimages.

Saints in heaven, pray for us. Merciful Lord, pray for us.

Callie Nowlin, MTS, is a regular contributor to the North Texas Catholic.

Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New American Bible, revised edition © 2010, 1991, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, D.C. and are used by permission of the copyright owner. All Rights Reserved. No part of the New American Bible may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the copyright owner.