Two ways to better hear that still, small voice

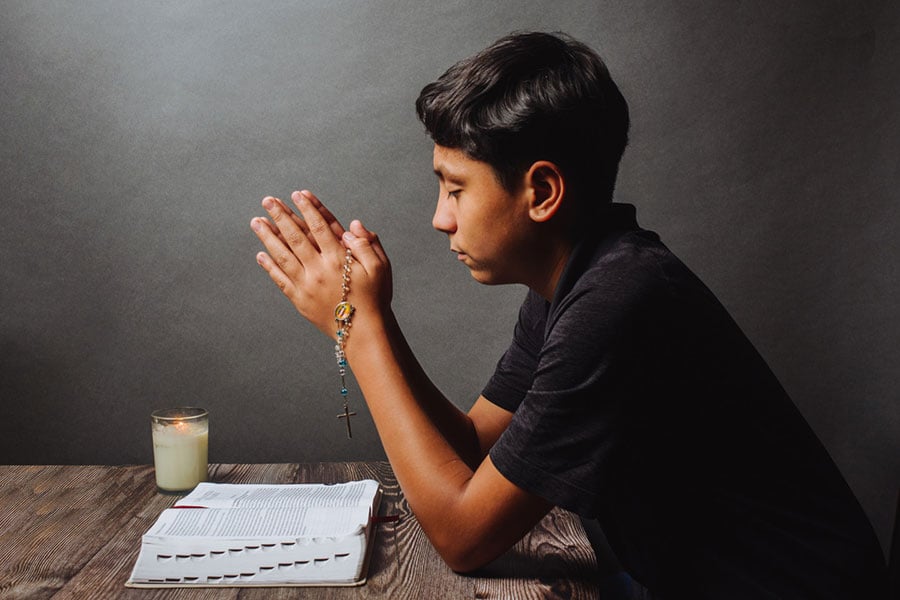

Cathopic.com/Gera Juarez.

Prayer has not always been easy for me. My experience with it has, at times, consisted greatly of confusion and frustration; not frustration with God, but rather with myself. I am often frustrated by obstacles that I, not any other, have laid in the path in front of me. Mostly, these are of a decidedly intellectual kind.

To give one example, I used to struggle with the idea of God as a distinct, personal creator, who plays an active role in the lives of His creatures. I blame this hang-up now, to a certain extent, on my largely introverted disposition, and consequent serial inability to relate completely to other people; and as God is, in a sense, the ultimate “person,” it would stand to reason I would run into trouble. However, as I have grown older, and the mysterious muscle which operates the faculty we call faith has, perhaps, been flexed a few more times, I’ve found it easier and easier to discipline my intellect, to tell it that some realities have always and will always continue to be out of my capacity to grasp. This is part of the reason why I take such great comfort in the written, recited, and liturgical/ritual prayers of the Church, by means of which, borne on the shoulders of countless generations of our forerunners in faith, we may be led securely and benevolently into the realm of the spiritual.

To extemporaneously compose and recite a verbal prayer “from the heart,” as it were, has for me proved quite vexing, and has generally only served to reawaken detrimental patterns of thought. Instead, the kind of prayer from the heart which never fails to give me consolation and remind me of the constant presence and activity of God is meditation. In a contemporary context, the word “meditation” tends to be associated with various New Age disciplines and pseudo-religions, with cheap self-help books and charlatans looking to prey upon our universal desire for something more. This is not the meditation of which I speak.

Unbeknownst even, I would venture, to many Catholics, a long and venerable tradition of meditation is endemic to the Church. It has been in existence for just about as long as the Church herself has, beginning with some of the first ascetics, who sought a life of prayer and solitude in the desert. By eschewing as many distractions as they possibly could, they hoped to better be able to hear that “still small voice.” One has to wonder what they would think of how many distractions we have to contend with today. Thankfully, isolating oneself in a desert hermitage is not required to benefit from the practice of meditation.

Meditation, I believe, can be viewed as a remedy for distraction, for spiritual forgetfulness, for preoccupation with the things of the physical world. What is intensely ironic, however, is how easily distraction itself “dis-tracks” us from the task of meditation. From the reading I have done on the subject, as well as by way of personal experience, the frustration of combating distraction is what keeps most people from engaging in meditation as a part of their prayer life. I am not in any way a spiritual director or advisor, nor do I hold any pretentions to that effect. However, I hope to offer some small advice that may aid you in the task.

One of the methods of meditation which I have found to have the most safeguards against distraction built into its very structure is Lectio Divina. Translated from Latin, it means “Divine Reading.” This is one of the most common forms of Catholic meditation, and for many good reasons. It consists of selecting a passage (or some passages) of Scripture, either the reading(s) for the particular day, or those of your own choosing, and reading the verses through multiple times. A common instruction I have come across is to read the passage(s) three times, which, in addition to being a high enough number to encourage the mind to find something new in each pass, is also nicely symbolic.

By focusing the mind on the task of reading, one naturally eliminates some of the causes of distraction, namely the lack of anything concrete for the brain to grasp and wrestle with. Lectio Divina is also, naturally, a great way to increase one’s biblical literacy. It may sound strange, but it can almost take on a hypnotic quality, with its reading and re-reading a set of verses, almost as though submersing the soul in a spiritual salve, letting it become as saturated as possible. The website BustedHalo gives a short summary of the subsequent steps of Lectio Divina: reflect, respond, and contemplate.

The second and last kind of meditation that I wish to recommend to you is even simpler than Lectio Divina but, I would say, just as beneficial to the over-hurried and distracted spirit. It consists of one action, a single directing of the will: pause whatever you may be doing, and know that God is all around you, ever present, ever active, ever creating, ever loving. Think, if only for just a moment or two, how you or anything that is real, could exist without the perpetual thought of God. What is a single, timeless moment for Him, stretches out to uncountable infinities for us. The feeling is like the comforting knowledge that one’s house rests on a sound, immovable foundation.

Our society would only benefit if more of us made a daily practice of either of these forms of meditation. It might force us to slow down, to not hold in such fascination the sight of landscapes whipping by outside the windows of our cars. We might more easily see the myriad ways in which God actively continues His creation in us and our environment. And, if we succeed in our fight against the attacks of distraction, that “still small voice” may be heard a little clearer.