Health care rooted in the Catholic Faith, Part 4: Catholics make major medical discoveries

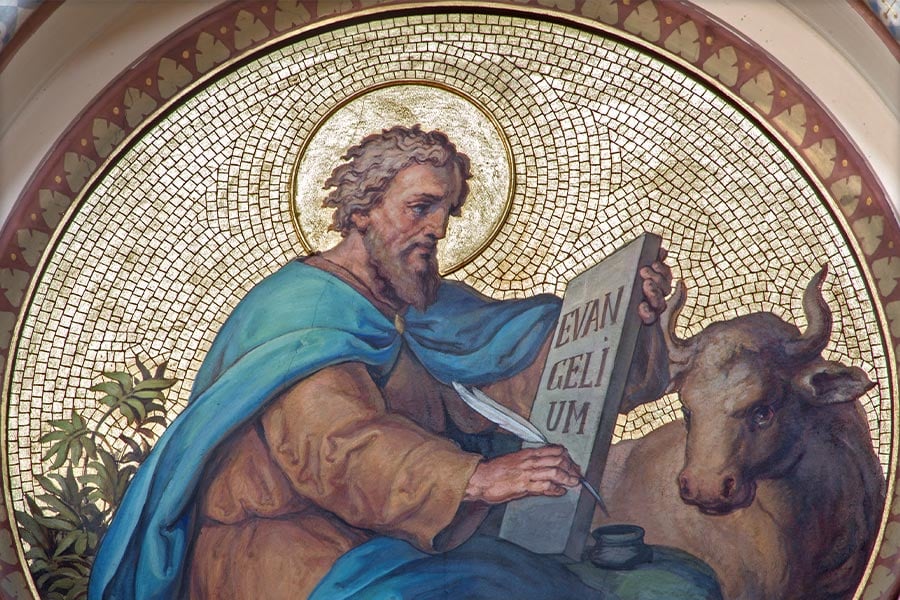

St. Luke the Evangelist was also a physician.

Throughout history, Catholics have been pioneers in the field of health care. The following are only some of the many followers of Christ who made major advancements in medicine, surgical procedures, and a better understanding of the human body.

Saint Luke the Evangelist (first century A.D.)

First century author of The Gospel According to Luke and credited with writing Acts of the Apostles, Saint Luke was also a physician. Although he did not travel with Jesus, he was a close associate of the Apostles. St. Luke’s missionary traveling companion, St. Paul, referred to him as “the beloved physician.” According to some historians, St. Luke might also have served as a personal physician to Paul during their travels. Many of St. Luke’s writings in the Bible give us insight into his medical background. Biblical scholars suspect that St. Luke studied to be a physician in Antioch, in Syria. As a physician, St. Luke could have had a comfortable life in Antioch, but instead chose to travel the world and endure hardships along the way as an early follower of Christ. A patron saint of physicians and surgeons, St. Luke is cited in the canon of the Mass, along with Saints Cosmas and Damian.

Saints Cosmas and Damian (circa 300 A.D.)

The Greek word “Anargyroi,” meaning penniless ones, is associated with these twin brothers who lived around 300 A.D. Talented and respected physicians, they never charged a fee to any of their patients. Born in Arabia, the brothers practiced medicine at the seaport of Ageae, now in Turkey, and in the Roman province of Syria. It is believed that the brothers were the first to successfully complete a limb transplant on a human being. Zealous Christians, esteemed in their community, they were eventually persecuted, tortured, and executed. Saints Cosmas and Damian are patrons of physicians, surgeons, and pharmacists. Along with St. Luke, the saints are cited in the canon of the Mass.

Saints Cosmas and Damian perform the miraculous cure by transplantation of a leg.

Bishop Theodoric Borgognoni (1205-1298)

A 13th century Italian Catholic bishop and Dominican friar, Bishop Borgognoni was one of the most accomplished surgeons in Medieval times. During his life, he devised an anesthesia formula that was one of most widely used for several centuries. The bishop also introduced basic antiseptic practices in surgery. He produced a four-volume work covering all aspects of surgical practices that discounted many of those handed down from the ancient Greek and the Arabian surgeons. His writing on the topic is regarded as a major contribution to Western medicine.

Girolamo Fracastoro (1478-1553)

In 1545 Pope Paul III nominated Fracastoro, who served as his personal physician, as medical adviser to the Council of Trent. The longest council ever convened by leaders of the Roman Catholic Church, participants met from 1545-1563. Together with another physician, Fracastoro advised that the council actually leave Trent, because a plague was raging in the northern Italian town. As a result, in 1547 the Pope moved the council to the city of Bologna. Fracastoro’s 1546 work, De Contagione et Contagiosis Morbis (On Contagion and Contagious Diseases) stated that infection results from tiny, self-multiplying bodies that can be spread by direct or indirect contact through infected objects, such as clothing, or can even be passed through the air over long distances. For this work, he is respected as a pioneer of epidemiology — the branch of medical science that deals with the incidence, distribution, and control of disease in a population. Fracastoro was the first to scientifically describe contagion, infection, disease germs, and the ways a disease is transmitted.

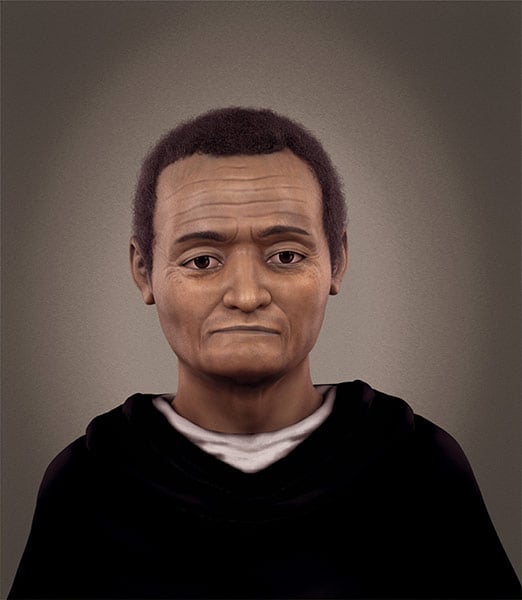

St. Martin de Porres (1579-1639)

A mulatto born out of wedlock in the 16th century, St. Martin de Porres grew up in poverty in Lima, Peru. At the age of 12, he was placed under the apprenticeship of a barber, where he learned to cut hair and practice the medical skills also expected in the profession, including surgery and dentistry. At the age of 15, de Porres joined the Dominican religious order. He later became a lay brother and earned the title “Martin the Charitable” for nursing the sick, as well as giving out food, clothing, and other essentials to the poor. Eventually, he was placed in charge of the order’s infirmary. He was known to have extraordinary healing skills, combining medical knowledge with unshakeable faith in the powers of God. He also possessed a truly Christian compassion in patiently caring for the sick. During an epidemic that swept through Lima, about 60 of the young friars became ill and were isolated in a remote section of the monastery. On numerous occasions, de Porres made his way through locked doors to care for them. He also served the sick outside the friary, sharing the same compassion he gave to his brothers. Miraculous healings are attributed to de Porres both before and after his death at the age of 60.

Rene Laënnec (1781-1826)

This French, Catholic physician invented the stethoscope in 1816. With his new medical instrument, Laënnec could hear sounds emanating from the heart, lungs, and other organs to help him make diagnoses. By listening to body sounds, Laënnec become a pioneer and proved to his contemporaries that he could identify cases of pneumonia, bronchiectasis, pleurisy, emphysema, and other lung diseases. He is considered the father of clinical auscultation — listening to sounds of the heart, lungs, and other organs with a stethoscope as a part of medical diagnosis. Laënnec perfected the art of physical examination of the chest and forever changed the way in which chest diseases are diagnosed.

Gregor Mendel (1822-1884)

The man widely known as the founder of the modern science of genetics was also a Catholic Augustinian friar and priest. Born in what is now the Czech Republic, Mendel spent his early years working on the family farm. As a young man, Mendel was inspired by a colleague at his monastery in Brno, also part of today’s Czech Republic, to study variations in plants. From 1856 to 1863 he grew and conducted tests on 28,000 plants, most of them pea plants. Mendel’s work helped to identify how recessive and dominant traits are passed from parents to offspring. Remarkably, he showed how these traits could be predicted mathematically. It would not be until 1900, 16 years after his death and 34 years after he published his findings, that the practical impact of his work would be recognized. His observations and insight established the rules of inheritance now referred to as Mendel’s Law.

Louis Pasteur (1822-1895)

A devout French Catholic, Louis Pasteur is probably best known for the process that bears his name — pasteurization. This heat treatment of food and beverages destroys pathogenic microorganisms. In milk, for example, the process destroys mycobacterium tuberculosis and other disease-causing microorganisms. Pasteur also produced the first vaccines for rabies and anthrax. He is often referred to as the father of microbiology. Many quotations about Pasteur give us insight into his faith. For example, he has been widely quoted as stating: “A bit of science distances one from God, but much science nears one to Him … The more I study nature, the more I stand amazed at the work of the creator.” In a biography of Pasteur, written by his son-in-law, Rene Vallery-Radot, the author said of the microbiologist: “Absolute faith in God and in Eternity, and a conviction that the power for good given to us in this world will be continued beyond it, were feelings which pervaded his whole life.” The author also wrote that Pasteur admired the life of St. Vincent de Paul. Some accounts state that at the time of his death in 1895, Pasteur was clutching his rosary while a loved one read to him the life of St. Vincent de Paul.

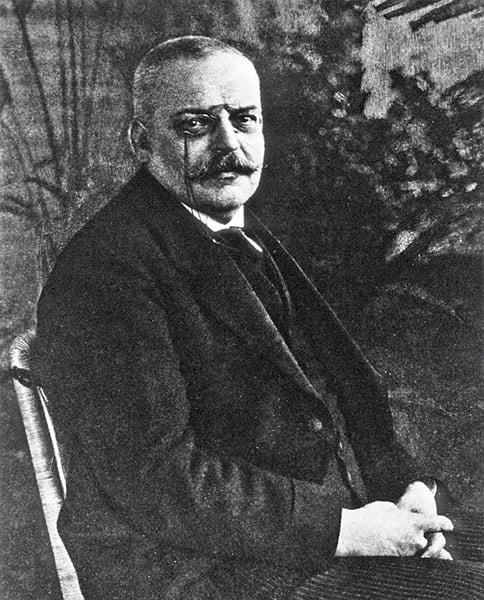

Aloysius Alzheimer (1864-1915)

Born in Bavaria, Aloysius Alzheimer was born in a Protestant community and his father insisted his son have a Catholic education. It was a good move as the youngster developed an interest in the natural sciences, including histology and pathology while at Catholic school. Eventually, Alzheimer earned his medical degree in Germany and began work at a state asylum. There he became interested in research involving the cortex of the human brain, leading to further education in psychiatry and neuropathology. In 1901, after meeting a woman exhibiting unusual behaviors and increasing short-term memory loss, Alzheimer focused his work on brain research, publishing many works on specific brain conditions and diseases. In 1906, the researcher identified a disease in the brain’s cerebral cortex that caused memory loss, disorientation, hallucinations and, ultimately, death. In 1910, the brain condition that the researcher had identified was named Alzheimer’s Disease.