Love endures: the charism of the Sisters of St. Mary of Namur lasts 200 years and counting

Sisters of St. Mary of Namur are seen in North Texas in this undated NTC file photo. (Colorized by Michael Sherman)

It started quietly with a sewing circle.

Two hundred years ago, in a European country ravaged by revolution, religious persecution, and turmoil, an ordained Cistercian monk came up with an idea to help the poor of Namur, Belgium. Two members of his St. Loup parish, skilled seamstresses who owned a tailoring shop, were known for leading prayer while fashioning garments with other like-minded women.

Josephine Sana and Elizabeth Berger, employees of the business, approached Father Nicholas Joseph Minsart about a religious vocation, despite the Belgian government’s prohibition of religious congregations. The innovative priest came up with a way the pair could discreetly pursue a vocation while helping desperate women learn a marketable trade. The priest found a small house in an impoverished neighborhood where the two faith-filled parishioners could live in community and teach sewing to girls while catechizing them. Lessons in reading and writing eventually became part of the workday.

The underground ministry’s good deeds soon attracted other kind-hearted volunteers and the group became known as the “Pious Ladies of St. Loup.”

As their numbers and influence grew across Belgium in 1819, the young congregation, now called Sisters of St. Mary of Namur, began the tradition of Catholic education and service to others that still defines the religious order today.

Celebrating the 200th anniversary of its founding, the international congregation has provinces in Belgium, England, Canada, Brazil, Congo, Rwanda, and the U.S. Enthusiastic members of all ages serve the Church and society as educators, missionaries, parish ministers, health care workers, spiritual directors, and immigration advocates.

“We began very humbly and simply in a little town in Belgium when a priest and a couple of laypersons saw a need,” said Sister Patricia Ridgley, a longtime pastoral staff worker at Dallas’ Holy Cross parish. Now retired, she joined the Sisters of St. Mary in 1960 after graduating from Our Lady of Good Counsel.

The little sewing school gave young, destitute girls a way to earn money other than begging or prostitution.

“To me, it’s a meaningful story even now,” asserted the former Bishop Dunne teacher and school board member. “Women have always been at the forefront of seeing a need and jumping in to do some small, little thing to help. God has blessed our congregation and we’re still doing some good in different countries around the world.”

New world, new beginnings

Missionary zeal to teach the poor and disadvantaged inspired five members of the religious order to journey to the New World in 1863. When America’s Civil War thwarted plans to travel west, they settled in Lockport, New York and established schools in the area to serve the German and Irish immigrant population. Ten years later, encouraged by Bishop John Timon of Buffalo and other supporters who recognized a need for Catholic schools in Texas, a group of sisters headed south to frontier settlements in the Lone Star State.

But the move to Waco in 1873 proved to be a different experience from their welcome in New York. The pioneer missionaries dealt with open anti-Catholic hostility from the Protestant majority, streets dirtied by cattle drives, oppressive heat, and tornadoes.

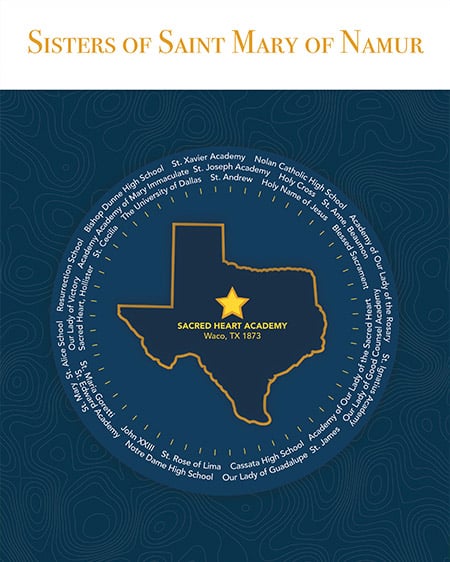

Despite those challenges, the Sisters of St. Mary of Namur founded their first school in Texas — Sacred Heart Academy — one week after arriving in Waco.

Always struggling and perpetually in debt, the religious order built a system of nine schools across North Texas over a span of 40 years — primarily with their own funds. Over the next five decades, the order established more schools at a record pace.

Changing Lives

Saint Joseph “San Jose” School opened in 1926 to serve children whose parents fled the religious persecution (the “Cristero” War) that followed the Mexican Revolution of 1910. Located in the heart of Fort Worth’s “El Norte” neighborhood, the predominantly Hispanic school lacked new textbooks and other teaching aids but consistently outshone its public counterpart, M.G. Ellis Elementary, in both academics and sports. San Jose later merged with All Saints Catholic School.

James Reza, who graduated from San Jose in 1952, credits the foresight and wisdom of the SSMNs for his successful career at General Dynamics.

“The majority of the kids who went to that poor, humble Catholic school became engineers, businessmen, nurses, or other well-paid professionals,” he said. “I attribute that to learning the basic foundation and comprehension of the English language.”

Many new students arrived at San Jose knowing only Spanish.

“From day one, the sisters versed us in English, and in a couple of weeks we were reading ‘See Spot Run’ in the old primer books,” added the All Saints parishioner. “They knew English was the language that would propel us into high school and get us into college so we could have a career.”

Living the Gospel message

Our Lady of Victory Academy (now school) is the only educational institution still owned and operated by the SSMNs. Originally housed in a five-story, red brick building on Fort Worth’s south side, the academy enrolled day and boarding students from kindergarten through junior college. Some pupils came from as far away as west Texas. OLV was also the first school to desegregate in Fort Worth.

The year was 1956, and, like other members of her order, Sister Louise Smith, SSMN, was teaching school in Texas.

“When Mother Theresa [Weber] announced it to us, it was a fait accompli,” recalled Sr. Louise, the archivist for the order’s western province. “Some of the parents objected and took their children out of the elementary school. Other parents admired what she wanted to do. It was a courageous decision for the time.”

Watching her teachers live the Gospel influenced Susie Reyes’ view of the world. Her parents, Loreto and Pedro Reyes, sent their five daughters to OLV in the 1960s and 70s.

“The way the sisters led their lives had an impact on my life as a Catholic and my service to the community,” said the grant writer for several nonprofits. “As I look back, their commitment to educating us went above and beyond.”

A 1974 Nolan Catholic High School graduate, another school the SSMNs founded, Reyes remembers the gentle prodding of her educators.

“They wanted us to succeed. We were always told to think ahead to college and the future,” she added, noting several classmates became doctors, lawyers, or other professionals. “It had an incredible impact on our lives.”

Sister Clara Vo, Sister Rosemary Stanton, and Sister Louise Smith at Our Lady of Victory Convent. (NTC/Juan Guajardo)

Outreach to Brazil

When Rosemary Stanton graduated from Nolan in 1967, her ambition was to join the Peace Corps. Thoughts of helping the underprivileged, in faraway places, appealed to the teenager. But, after attending the University of Texas at Arlington for a year, the college freshman made a different decision.

In 1968, she joined the Sisters of St. Mary of Namur and began a journey that would take her to the order’s missions in Africa and Brazil.

“We did a lot of social work to help out the people, as well as evangelization,” explained Sister Rosemary Stanton, SSMN, who spent 34 years as a missionary.

The congregation’s first outreach in Brazil was in the northeastern part of the South American country.

“We lived in one of the many towns that belonged to one big parish with no resident priest,” she said, remembering the villagers who worked hard to survive.

The Brazilian bishop asked the sisters to administrate parish life so the Eucharist could stay in the church.

“A priest would come once a month and between those times, our sisters took care of the parish,” Sr. Rosemary continued. The Fort Worth native returned home in 2002 and is now part of the campus ministry team at her alma mater. She prepares liturgies, trains Eucharistic ministers, and provides resources for theology classes along with other pastoral duties.

Many Nolan students never had contact with a religious sister in elementary school. Sr. Rosemary’s presence on campus fills that void.

“My gift of being a Sister of St. Mary for 51 years has been the people I’ve been blessed to live among and the people I have ministered to,” she explained. “For me, it’s all about the people.”

Strong ties

After living with another congregation in Mexico, Sister Yolanda Cruz began the process of becoming a SSMN in 2001 and professed final vows in 2005. What attracted the New Jersey native to the Fort Worth congregation?

“I saw their joy and simple ways,” Sr. Yolanda enthused. “They were so pastoral in their ministries and I saw their deep presence in the diocesan Church. People gravitated to them and I gravitated to them as well.”

The former vice chancellor and delegate for women religious for the diocese is now a faculty member at the University of Dallas’ Neuhoff School of Ministry.

Passionate about mission and catechesis, Sr. Yolanda initially balked at the idea of becoming a college professor.

“Never saw myself in an academic setting,” she admitted. “I thought it would limit my interaction with the community at large and the Church.”

But her order’s strong ties to the Irving university changed her expectations. The western province of the SSMNs teamed up with two Dallas businessmen to open UD in 1956 with the blessing of Bishop Thomas Gorman. Several sisters were part of the original faculty.

“It’s humbling to follow in the footsteps of the other sisters who taught here,” said Sr. Yolanda, who teaches theological courses in Scripture online and in the classroom. “We’re embedded in this university.”

Sister Yolanda Cruz, Provincial Gabriela Martinez, and Sister Ines Diaz stand in the chapel of Our Lady of Victory Convent. (NTC/Juan Guajardo)

Welcoming Hispanics

When Sister Ines Diaz came from Mexico to the U.S. to join the Sisters of St. Mary of Namur in 2010, she helped provide outreach to Hispanic families at St. John the Apostle and Holy Name parishes.

“It was common to see people who were baptized but didn’t have other sacraments,” she pointed out.

Offering RCIA and sacramental preparation classes and materials in Spanish persuaded more Hispanic Catholics to re-engage with the Church. She later continued that mission as director of Hispanic Ministry for the diocese. Today Sr. Ines works as co-coordinator of the SSMN convent and is pursuing a master’s degree in Bible studies. The seasoned catechist hopes to lead Bible classes in Spanish.

“Helping Hispanics come back to the Church is my passion. I feel very blessed and very energized to do it,” she said. “By coming here, I filled a need and hope to continue this part of my vocation.”

Finding peace

An unexpected death changed Sister Francesca Walterscheid’s life as a SSMN.

She was teaching first grade at St. Cecilia’s School in Dallas when Sister St. Mark, SSMN, who supervised the convent’s infirmary, died in a tragic car accident.

“We worked together on weekends, so I kind of knew what was going on,” said the 91-year-old, remembering how her responsibilities shifted from the classroom to health care in 1978. “I missed teaching but kept busy working with the sick.”

She learned how to move patients and bandage wounds from watching Sister Elaine Breen, SSMN, a registered nurse. They also attended workshops on geriatrics together.

Taught by the Benedictine sisters in Muenster, the Sacred Heart graduate looked into different religious orders after high school before choosing the SSMNs. She was drawn to the congregation’s hospitality and simple ways.

“I felt at home and at peace,” Sr. Francesca recounted. “If you find peace, it’s a good sign that it’s a vocation because you never know when you enter. It’s a leap of faith.”

The former nurse’s aide sat at the bedside of many sisters who were dying and said it was a privilege to care for them in their final days. The “letting go” is always peaceful.

“They know what’s important in life,” she explained. “That’s how we’re all supposed to live.”

Sister Roberta Hesse, Sister Mary Dorothy Powers, Sister Francesca Walterscheid, and Sister Charles Marie Serafino. (NTC/Juan Guajardo)

Witnessing genocide

When you ask Sister Charles Marie Serafino what inspired her to become a missionary, she remembers watching old Maryknoll movie reels with her seventh-grade geography students at St. Maria Goretti Catholic School. The films, produced to highlight Catholic missions overseas, provided surprising details about life in South American and African countries.

“Growing up in Duncanville, I had this narrow vision of the world. Those Maryknoll films enlightened me,” the former teacher explained. “I started questioning the injustice in the world and the gap between rich and poor.”

The SSMNs have ministered in Africa since 1923, so the idea of serving the poor in another country seemed possible. Her request to begin mission work was finally approved, and in 1964 she left Texas for her first assignment at a girl’s boarding school in Rwanda.

“It didn’t have any running water or electricity and we had to chop wood to cook,” Sr. Charles Marie said, describing the primitive conditions. “All of those material needs were very preoccupying.”

Her 38 years in Africa included time in the Congo where she was director of novices — a task that continued after returning to Rwanda where a new novitiate was started on the other side of the country.

Although she calls washing clothes in a stream with tribal women or helping villagers prepare for marriage or first Communion “real mission moments,” an enduring memory is living through 100 days of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. Ethnic Hutu extremists killed more than 800,000 members of the minority Tutsi tribe during the mass slaughter.

Avoiding danger, Sr. Charles Marie and 24 other sisters — some from another congregation fleeing harm — hid in the woods or the SSMN’s mission house in Kiruhura. They lived on oatmeal, cooking oil, and whatever vegetables were growing in the garden.

“Several times the militia, dressed in huge banana leaves, came running through our property with clubs and machetes,” she said, recalling the experience. “There was the anguish of not knowing what would happen next. People were being massacred all around us.”

Eventually, some members of the group were flown via helicopter to Congo. Sr. Charles Marie escaped by driving a Suzuki — packed with sisters — into neighboring Burundi. No members of her order were lost but other congregations suffered casualties.

Talking about the Rwandan genocide is still difficult for the longtime missionary.

“Being with the villagers outside, under the night sky, and watching them dance and sing — those are the moments I try to remember,” Sr. Charles Marie emphasized.

Being present

“Working in Africa, I received so much more than I could ever give. It wasn’t as much about nursing as it was learning the value of just being present.”

That’s how Sister Roberta Hesse, SSMN, described the years spent working with families in Rwanda, the Congo, Cameroon, and Tanzania.

“Everywhere I went I got to know the people on a very personal level by just being with them,” she explained. “Even if I didn’t know how to do their work, I would just sit with them.”

A licensed vocational nurse, the Muenster native spent much of her time treating children who suffered from malnutrition or tuberculosis. Sitting in the mission’s nutrition center, the sister’s heart would ache to see malnourished children walk in with a mother who often carried another baby on her back.

“They were wonderful people, but their lives were hard because of the lack of food and not much space,” Sr. Roberta said, explaining how a large tract of land became smaller as it was divided between family members.

Women did all the farming, so she taught them about crop rotation, distributed vitamin pills, and fed the children powdered milk mixed with ground sorghum and a little sugar.

“The children loved it and they gained weight,” Sr. Roberta remembered. “As they grew healthier, their mothers wanted to know more about nutrition. That was always a positive thing.”

During her 34 years on the continent, the families she met weren’t very different from those in the U.S.

“The hearts of African mothers are exactly like mothers here and in other parts of the world,” the missionary said. “They want the best for the children. They want them to be healthy, educated, and to make something of their lives.”